Valuing Timeouts in Football

What is the (Universal) Value of a Timeout?"

in r

January 13, 2016

On December 27, the Pittsburgh Steelers were down 13-3 against their rivals, the Baltimore Ravens, after the first half. The Ravens opened the second half with the ball, but quickly punted the ball following a three-and-out drive. On the following possession, the Steelers took over the ball on their own 21 yard line, and made a short gain followed by an incomplete pass. Facing second and 5 from their 26 yard line, Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger had a problem: the play clock was winding down and the team was not yet set. Facing a potential delay-of-game penalty, Roethlisberger made what he thought to believe the logical decision - he called timeout.

Watching this game on TV, I was immediately frustrated by this decision. We were just 1:28 into the third quarter; why waste a timeout so early in the half? Don’t the Steelers know timeouts are more valuable at the end of the game, that they should be preserved in case they need to make last-minute march down the field to secure victory? Maddeningly, the Steelers did this again on their next possession. With still 7:55 left in the third quarter, Roethlisberger burned another timeout in order to prevent a delay-of-game penalty. The Steelers would have to play the rest of the second half with just one precious timeout left. I, like many others, was baffled by these decisions.

Coaches and players face this strategic decision frequently during a football game. Generally speaking the offense has either 40 or 25 seconds from the start of the play clock to begin their next play. Ideally they will start their next play with plenty of time left on the play clock (or perhaps intentionally run the play clock down when they hold a lead late in the game). If the offense fails to snap the ball before the play clock expires, then the officials assess a delay of game penalty which moves the ball back 5 yards. In many situations where the play clock is about to expire and the offense doesn’t appear ready to snap the ball in time, either the quarterback or a coach will call timeout rather than allow the delay of game penalty to be called. While this is the conventional wisdom, is it really the optimal strategy?

On its face, this question is relatively simple. In order to make the optimal decision, one should compare the win probability added (WPA) of calling the timeout versus taking the delay of game and losing 5 yards. If the WPA is higher for the timeout scenario, then call the timeout. If the WPA is higher for the delay of game, then take the delay of game and save your timeout. There are many different ways to estimate the probability a team will win a football game. Typically these models account for factors such as the down, distance, field position, score, and time remaining. Others incorporate additional information such as the relative strength of the teams (usually based on the Vegas line). However very few explictly account for the number of timeouts remaining (either for the offense or defense). Without doing so, all we have is an argument based on assumptions, rather than comprehensive evidence.

That is not to say that people have never examined this question. FootballCommentary.com uses a Markov decision process and dynamic programming to estimate the clock-management value of a timeout. While their approach can be used to decide between taking a timeout or the delay of game penalty, I find it difficult to interpret and not easily replicable. Brian Burke, formerly of Advanced Football Analytics and now a Senior Analytics Specialist at ESPN, wrote on valuing timeouts back in 2014. In a two-part series of articles on this topic, Burke laid out a general approach for estimating the value of timeouts.

To estimate a timeout’s value, we just want a good estimate of how often a team wins in some situation with n timeouts compared to how often a team wins in the same situation with n-1 timeouts. The difference in how often a team can be expected to win in each case is our result–the WP value of the timeout.

The biggest difficulty in this approach is that we know lots of other factors – down, distance, field position, score, time remaining – also influence the outcomes of games. In fact, timeouts probably have a much smaller influence on win probability than these other factors. In order to isolate the effect of timeouts, we need to control for these other factors in some way. Burke makes this estimation by first limiting his observations to a set of similar plays (all situations where the offense was up by 0 through 7 points and had a first down between their own 40 and the opponent’s 40 in the 3rd quarter). Because all of these plays are similar to one another, we can get a rough approximation of the change in win probability as teams use up their timeouts. Using this approach, Burke estimates the value of a team’s first timeout to be +.05 WP. Applying this to our question, unless the delay of game penalty costs a team more than -.05 WP, then an offense should allow the play clock to expire and take the penalty.

However, we cannot stop there. As Burke notes, this is an extremely crude approximation of the value of a timeout and includes several assumptions which may not be true. First, it assumes that more timeouts is always better.

While this is generally true (from 2001-14, the team with the most timeouts at the end of the game wins 90% of the time, compared with just 42% of teams with fewer timeouts), it is not a universal constant, especially when considering the influence of timeouts taken earlier in the game. For instance, a team may use its timeouts early in the third quarter (such as the Steelers in the example above), yet still go on to win the game (not like the Steelers above). However the more problematic assumption is that the value of timeouts is equivalent. That is, the difference in value between 3 and 2 timeouts is the same as the difference in value between 2 and 1 timeouts is the same as the difference in value between 1 and 0 timeouts. Again, this may not always be true. A team which needs to make a two-minute drill to win the game would greatly appreciate having at least one timeout; doing so opens up their playcalling to allow for run plays or open field passes rather than only attempting plays which can easily stop the clock. So the change in win probability from 0 to 1 timeout is substantial. While having 2 timeouts is even better, it’s not necessarily true that having 2 timeouts is precisely twice as good as having just 1 timeouts; that is, the effect of timeouts on win probability isn’t strictly linear.

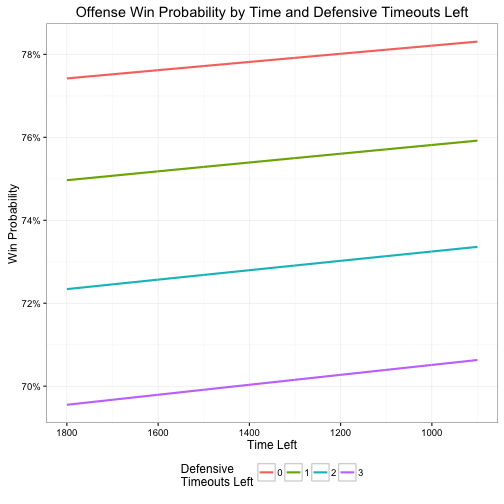

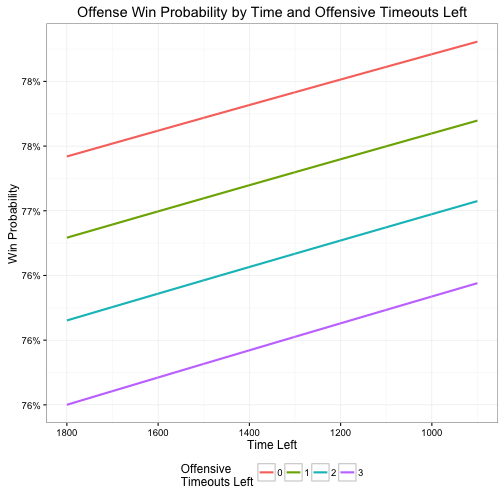

Burke recognizes these shortfalls and generalizes his methodology by employing logistic regression to estimate the WP of a timeout. This approach models winning {0,1} as the outcome/dependent variable and distance from own goal, score difference, time remaining, and timeouts for the offense and defense as predictors. Again, we limit the model to a set of similar play types to isolate just the effect of timeouts. Below, I replicate this approach using data from Armchair Analysis for the 2002-14 seasons, while again limiting the model to all situations where the offense was up by 0 through 7 points and had a first down between their own 40 and the opponent’s 40 in the 3rd quarter (number of plays = 3560).

Here I find an effect on par with Burke’s original estimate. The untransformed coefficient for -0.14 for defensive timeouts, close to Burke’s -0.111. However the coefficient for offensive timeouts is even stranger at -0.04. This suggests that as an offense’s remaining timeouts increase, its win probability decreases.

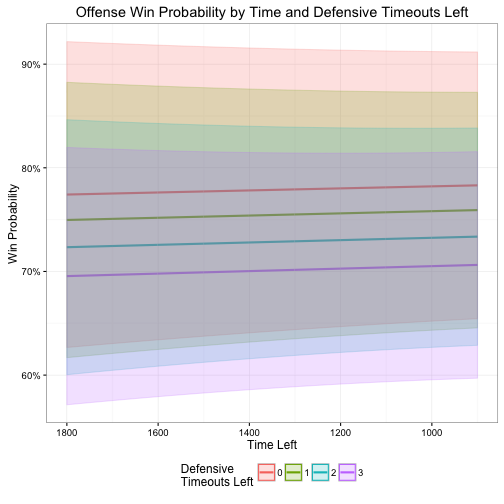

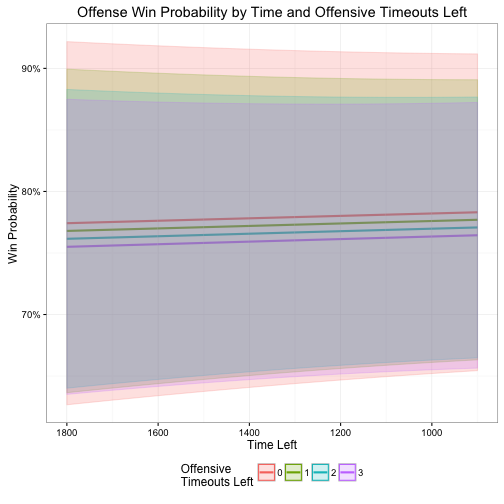

Furthermore, neither of these coefficients are significant based on their standard errors. This is most easily seen by redrawing the two plots, but this time incorporating the standard errors as well. The overlapping error bounds clearly show no substantial relationship between remaining timeouts and win probability.

Hmmm. In theory (an apparently in practice), this approach should have worked. While I am not using the exact same data set as from Burke’s original analysis, the Armchair Analysis data is well documented and reliably used in many different applications, including the NYTimes 4th Down Bot. I attempted several different reliability checks to see if my data filters were causing these extreme differences, however I could not uncover any reason to explain this discrepancy.

This suggests a few different possibilities. The first is that timeouts simply do not influence winning in the NFL; I don’t believe this to be the case, otherwise why else would they be included in the rules of the game? Perhaps instead their value is overhyped, or maybe they just aren’t useful to predict game outcomes for the specific game situation we just analyzed. Here I think there may be more support. The fact is that in the third quarter, relatively few teams use their timeouts. There may simply not be enough variation in timeouts available to reliably estimate the effect of timeouts on winning given this game situation. Below is a table of the number of plays in the regression model above for each given number of timeouts for the offense (columns) and defense (rows). The vast majority of observations are where each team still has all three timeouts.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 16 |

| 2 | 1 | 16 | 57 | 315 |

| 3 | 2 | 34 | 342 | 2762 |

Even if such an approach works for some situations, you still have to slice and dice your data to estimate a separate model for each game situation. Not very helpful if you want to quickly estimate the value of the timeout across many different game situations.

What would be really useful is a method to calculate the importance of timeouts for any given game state. Given this knowledge, coaches and players could then make informed decisions. First and 10 on your own 20 yard line with 5:33 left in the 3rd quarter and the play clock is about to expire - do you call a timeout or take the delay of game penalty and save your timeout for later? You’re on defense and the officials just awarded a first down based on a questionable completed pass call - do you challenge the play to try and overturn the ruling, or pocket it knowing you might not win and will be forced to burn a timeout?

That would be fantastic, if such a method existed. Fortunately there might be a way. Next time I’ll lay out such an approach.